Facilitating a hackathon

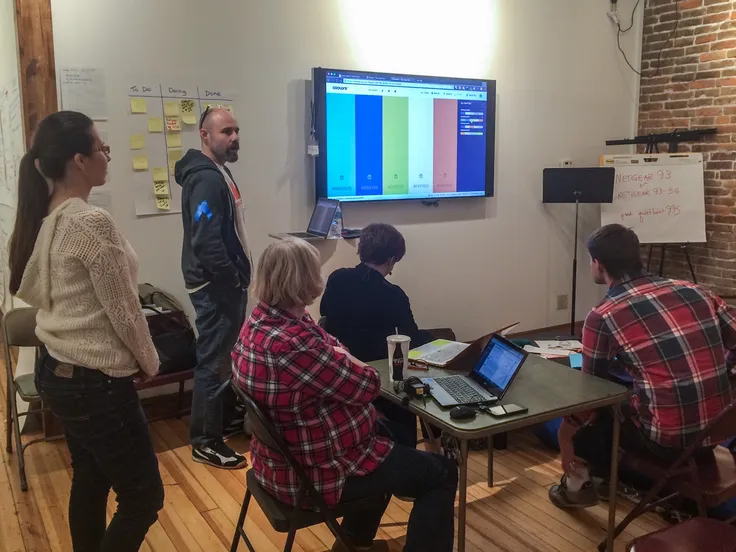

In late February, Bloomington hosted a 3-day hackathon with the goal of designing, building, and launching a website for Indiana.com. It brought together about 20 professionals and students with expertise in design, development, writing, curation, legal practice, and business.

I joined as one of four staff to assist with the weekend’s activities. Being trained in Agile Scrum software development techniques and as a member of practicing teams for the last 2.5 years, I possess skills and perspective distinct from my fellow staff. I would rely on this expertise to assist me in my primary role as a facilitator of team processes. Essentially, I was to be a Scrum master.

Agile teams often iterate in sprints of two week increments over the duration of a product’s lifetime. How does this scale down to fit sprints of at most 2 hour increments over a weekend? Agile teams spend numerous sprints melding and struggling as a team before getting into a groove and being productive. In the timeframe of a hackathon, there is no time for team dynamics to take root. I asked a colleague and Scrum master for advice. He encouraged to “incrementally layer in complexity” and to “experiment, adapt, and (at least initially) err on the side of over communicating.”

My only experience with a hackathon was as a participant in 2011, in which many small teams launched separate non-profit websites. As the facilitator for a hackathon with the goal of launching a single website with one large team, I didn’t have much direct past experience to rely on. The Hackathon Guide was the best single resource for preparing for the event, but its focus was directed at organizers, not facilitators.

While I initially felt unprepared, it was helpful knowing that everyone who participated felt the same way. The weekend would become whatever it would become. All I could do is try, and if things didn’t work, then iterate until something did work.

In my facilitation role, I fulfilled three primary duties: I helped the team to communicate well and often. I helped the team to make decisions. I helped the team to stay engaged throughout the grueling 33 work hours.

I will describe what worked well and what didn’t work well, then suggest what could be done next time. I hope my experience can assist others better prepare if they would find themselves in similar circumstances.

Regularly check in

Throughout most of the weekend, participants organically divided into three functional groups: design and development; content curation and writing; and business and marketing. It was important to structure opportunities for regular communication, especially since most participants were unfamiliar with each other, in either a social or professional manner, and since most every person wasn’t participating during all hours of the event. Every 2.5 hours or so, everyone would gather in the same room for a standup meeting and respectfully listen as each person would answer three questions:

- What have you done?

- What will you do?

- What is hindering you?

Since most were unfamiliar with standup meetings, it was helpful to write these questions on a poster, hung on a prominent wall. Answers to Question 3 were written on a whiteboard, labeled as blockers. If responses turned into conversations, then they were marked down as parking lot items to continue following the meeting. As blockers and parking lots are resolved, they’re erased from the board.

While everyone had the opportunity to speak, not everyone did, since their answers would just mimic another’s, who they worked closely with since the last meeting.

Though the poster helped everyone answer the questions, it didn’t enforce brevity. Responses would ramble, wouldn’t always directly address the questions, and would frequently lead to conversations among several individuals. Each violation of the meeting protocol ate at precious time, stealing from every participant. Meetings lasted 10–20 minutes, but they should have been under 10 minutes. As a facilitator, I should have been more strict with enforcing time limits. Budgeting 45 seconds per person (15 seconds per question) would have helped considerably.

The next meeting time was determined immediately following the current meeting. This allowed more flexibility in the schedule for mental breaks and food, but the inconsistency made it more difficult for returning participants to quickly orient to the work in its given state. Perhaps quicker and more regular meetings would result in greater collective confidence in our progress.

Communicate realtime

Throughout the weekend, groups separated between two primary workspaces in adjacent buildings. Especially with this disjoined arrangement, it was necessary to have some standard method of realtime communication. Slack was the perfect solution. Public and private channels isolated discussions concerning each group of work. Individuals could track and join conversations, engaging at their pace, wherever they may be.

While individuals may quickly learn names within their group of peers, it was increasingly difficult to remember names for those in sibling groups. Name tags were tethered to their owners on lanyards, but after the first day, their annoyance outweighed their utility. I asked participants by name to speak when it was their turn during standup meetings, for the sake of everyone learning each other’s name. This feeble effort was never sufficient. Without everyone knowing names, it became difficult for individuals to ask others to join them in parking lot conversations. It contributed to an anxiety that felt that if the discussion didn’t happen immediately during their time at standup, then the opportunity for conversation would be lost once the team split back into working groups.

Slack could be a decent method to learning names. Assuming team members assign photos to their profile and everyone displays full names instead of usernames, then names and faces will be paired whenever a virtual conversation occurs. This continual reinforcement would supplement normal social interactions well.

Track progress

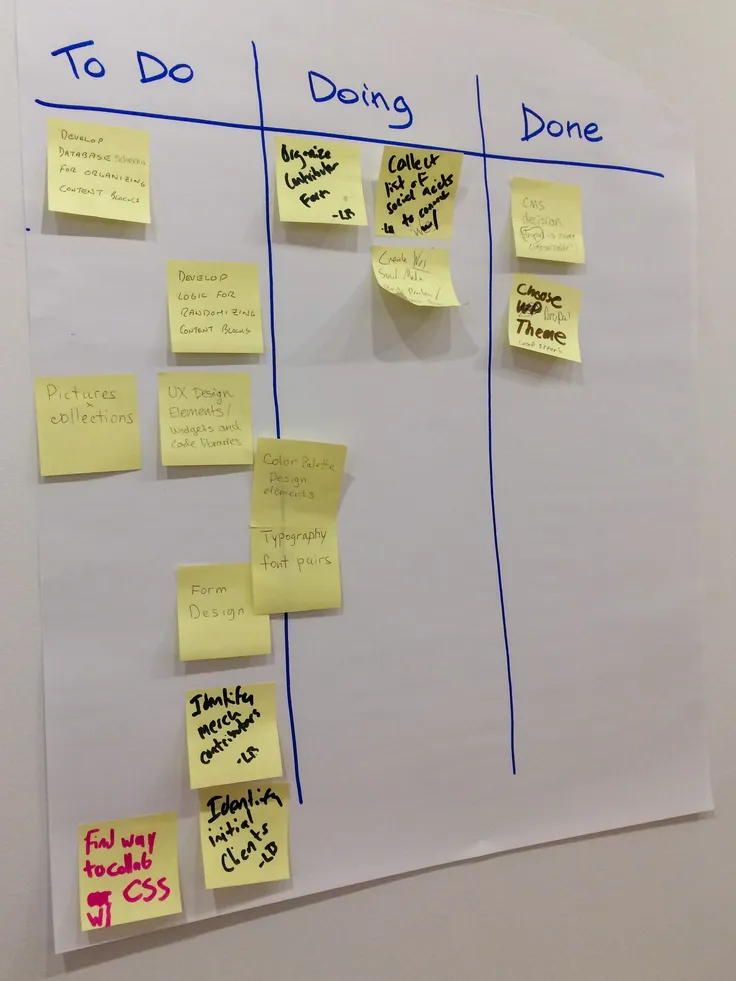

The start of Saturday kicked off assignments of work to individuals and groups. Due to the diversity of work needed, the design and development group especially needed some method of tracking progress, and a Kanban board provided the most appropriate structure. A poster board was divided into three columns, labeled as To Do, Doing, and Done. Participants wrote down tasks on sticky notes, discussed them and refined them, then placed them in the To Do column. Individuals would sign their name to tasks they claimed, whenever it was ready to be started. When tasks complete, they rest in the Done column. Before assigning oneself to another task in the To Do column, they must first contribute to anything in the Doing column, if possible. At a glance, those within and outside of the working group can see the progress of tasks shift from left to right.

The Kanban board worked well on Saturday, but its use waned as the weekend progressed. The board wasn’t being updated, and it didn’t always reflect what was being said during the standup meetings. Participants would depart from the event for hours at a time, and others may not be knowledgeable or aware enough to continue tasks. Tasks became blocked by third party hindrances that would not be resolved during the weekend. To Do tasks lingered when the person who wrote them wasn’t available to explain their purpose in more detail when another was ready to own a task.

While the board was useful, it was only as useful as participants were willing to devote to it. Participants should more thoroughly discuss expectations about tasks before rushing into work. The board should be updated before each standup meeting. Time estimates, assignees, and blockers should be marked on tasks.

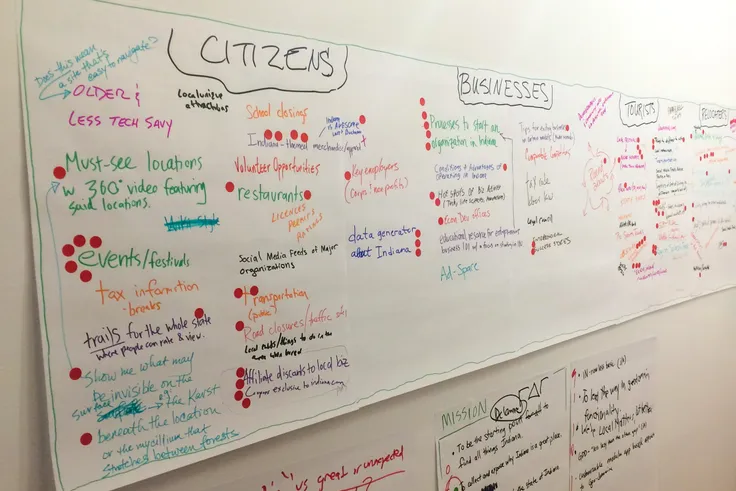

Distill concepts

Much of the first half of the hackathon involved generating concepts for the company’s mission and the weekend’s product. For these exercises, participants were allocated time to anonymously contribute to the pool of concepts. Once idea generation started to settle down, participants silently absorbed the concepts and then voted for the most compelling ones using an allotment of six red dots. The results of this dot voting reduced the concepts to a more manageable subset of ideas, which then were further refine during an open discussion.

To keep the voting pure, no one should be influenced by knowing the person who contributed the concept. However, participants inevitably asked for clarification, and an answer demanded the contributor to respond. Such responses often twisted into an idea pitch or plea, rather than adhering to an objective explanation.

Because concepts weren’t vetted before voting initiated, many concepts overlapped, causing votes to be split among concepts perceived to be equivalent. In that way, stronger but similar concepts were closer in count to weaker but unique concepts.

These and other issues with dot voting are well known.

Although it would demand more upfront time, dot voting would probably be more effective if concepts were initially consolidated and presented in a way that didn’t require commentary to be understood.

Make decisions

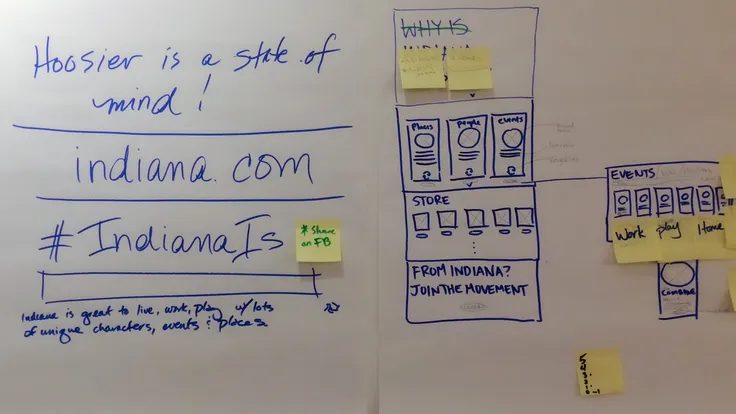

By mid-Saturday, progress started to stagnate. Most of the team was wanting to proceed with a concept, while one thought the decision was premature. After some deliberation, I interrupted and provided a mechanism known as thumb voting to come to a resolution. Using this method, the team agreed to devote 20 minutes for additional sketching, before the technique was used again to choose a concept. It turned out most of the newly generated ideas were just refinements or enhancements that would be infeasible to work on during the limited timeframe of the weekend.

When team decisions, such as just described, cannot be quickly or confidently determined, thumb voting can help to effectively arrive at a consensus. A team member shares a proposal, and all team members silently determine how they will vote. After a count, everyone will simultaneously vote one of three ways with a hand: Raising a thumb up means the individual is fully supportive of the proposal. A thumb directed sideways means the individual will accept the proposal, but they may have reservations about it. A downward thumb means the individual rejects the proposal. Proposals are accepted as decisions only if everyone voted with a thumbs up or sideways. Those voting with a thumb down must explain what it would take for them to change their vote, and it is the responsibility of the proposer or a moderator to facilitate a resolution. If that discussion results in a new or amended proposal, then voting starts again until a proposal is unanimously accepted as the decision.

Thumb voting is conceptually identical to Agile’s “Fist of Five” voting, except that voting options are consolidated to minimize the chance of analysis paralysis.

Value participation over tools

A content management system would be needed to regularly maintain and contribute to content on Indiana.com. Early Saturday, four developers came together to determine an appropriate open source platform. The debate soon narrowed between WordPress and Drupal. Drupal is perceived to be more limber than WordPress, and therefore, it would be more welcoming to whatever design direction is chosen. The one developer who was most familiar with Drupal was confident in being able to quickly train the other three. Despite the three being more familiar with WordPress, the one developer persuaded the others to commit to Drupal.

The remainder of the weekend emphasized how misguided that initial technical decision was. Time during the weekend was needed to be spent building, so most Drupal training was abbreviated at best. The three non-Drupal developers were frustrated with the new technology and were generally unhappy, while the one Drupal developer was overwhelmed, weighted with the full burden of the weekend’s ambition. The Drupal developer attempted to make up the difference by working alone throughout Saturday night, but such hopeful productivity never occurred due to burnout. Returning late morning on Saturday, the Drupal developer was able to progress further, but there wasn’t the momentum that was needed to strongly finish the weekend, nor was there the expertise of other Drupal developers to productively share in the work.

The choice of technology was perhaps appropriate for the longterm of the website, but it was not the correct choice for accomplishing the goals of the weekend. Since there was no guarantee about the continuation of the product outside the hackathon, most decisions should be framed with an expectation that the work is merely a prototype, meant to get quick, cheap, and tangible results. A prototype provides guidance, tests viability, and is disposable. Productivity and morale would have been better if WordPress was chosen, even if the platform was eventually swapped for Drupal. As it was, the decision violated the first principle of the Agile Manifesto, in which “individuals and interactions” should be valued “over processes and tools.” The choice of tool should be primarily influenced by how well it aids collaboration and relationships within the team, and the choice of Drupal did not uphold that ideal.

Conclusion

A facilitator should protect the team, especially from itself. Decisions should be made based on what will provide the happiest experience for participants during the weekend. The weekend is grueling and difficult enough. The outcomes of decisions should maximize the social good of the team.

Ensure more than one person can contribute to any piece of work and can continue another’s work. Don’t allow any one person to become a bottleneck. Assume there will be attrition of both participants and energy throughout the weekend.

Shift among working groups, find those who are disengaged, and get them engaged: be that assigning work, removing hindrances, encouraging breaks, or whatever is needed.

Brutally budget time, and brutally protect each person’s time. Use timers to time box activities. Defer conversations incurring in a group that truly involve only a subset. Prepare accounts for essential services before the hackathon (such as Slack, Google Docs, GitHub, and a hosting provider), even if the team would choose to not use them.

Introduce tools and processes as needed to assist the team in effectively communicating, making decisions, and producing quality work. The team should iterate the product quickly and often, and get something in the world so it can be responded to. It is better to quickly create something incomplete than to eternally ruminate the fantastical.

Act as mortar to the bricks that are the participants. Be the glue that keeps the team sturdy. Fill in the gaps, wherever there is need. Be a catalyst to strengthen the team. Uphold the integrity of the team.